The history of Saint Martin / Sint Maarten shares many similarities with other Caribbean islands.

Its first inhabitants were Amerindians, followed by Europeans who brought slavery to exploit commercial interests.

Early Days History

The ancient relics date back to the first settlers on the island, probably Ciboney Indians (a subgroup of the Arawaks), 3,500 years ago.

Then another group of Arawaks emigrated from the Orinoco Basin of South America around the year 800. Because of the salt marshes of Saint Martin, they called it « Soualiga » or « Salt Land ». Primarily farmers and fishermen, the Arawaks lived in straw villages with houses with roofs strong enough to withstand hurricanes.

Their civilization valued artistic and spiritual activities. Their lives, however, were disrupted by the descent of the Caribbean Indians from the same area of origin. As a warrior nation, during the history, the Caribbean killed Arawak men and enslaved women.

When Europeans began to explore the Caribbean, the history had almost completely replaced the Arawaks.

Colonial Era’s History

In 1493, during his second voyage to the West Indies, Christopher Columbus named it Isla de San Martín in honor of St. Martin of Tours, because it was the first time on November 11, the day of the festival from Saint-Martin.

However, although he claimed it as Spanish territory, Christopher Columbus never took possession of the island and Spain has made the colonization of the island a minor priority. The French and the Dutch, on their side, coveted the island. While the French wanted to colonize the islands between Trinidad and Bermuda, the Dutch found that Saint Martin was halfway between their colonies of New Amsterdam (now New York) and Brazil.

With few people living on the island, the Dutch easily founded a colony there in 1631, erecting Fort Amsterdam as a protection against the invaders. Jan Claeszen Van Campen became his first governor of the history, and shortly thereafter the Dutch East India Company began its salt extraction business.

French and British colonies have also emerged on the island. Taking note of these prosperous colonies and eager to maintain their control over the salt trade, the Spaniards now found Saint Martin much more attractive.

It was the 80 years war between Spain and the Netherlands.

Spanish forces captured Saint Martin from the Dutch in 1633, seizing control and driving most or all of the colonists off the island. At Point Blanche, they built Old Spanish Fort to secure the territory. Although the Dutch retaliated in several attempts to win back St. Martin, they failed.

Fifteen years after the Spanish conquered the island, the Eighty Years’ War ended. Since they no longer needed a base in the Caribbean and St. Martin barely turned a profit, the Spanish lost their inclination to continue defending it.

In 1648, they deserted the island. With St. Martin free again, both the Dutch and the French jumped at the chance to re-establish their settlements. Dutch colonists came from St. Eustatius, while the French came from St. Kitts.

After some initial conflict, both sides realized that neither would yield easily. Preferring to avoid an all-out war, they signed the Treaty of Concordia in 1648, which divided the island in two.

The History of the Concordia Treaty, signed by both countries, agreed that under this agreement, French and Dutch settlers would coexist in a cooperative manner, according to eight criteria to respect.

History of the Legend…

During the history, a legend grew up around the division of the island. According to this legend, in order to decide on their territorial boundaries, the two sides held a contest. It began with a Frenchman drinking wine and a Dutchman drinking jenever (Dutch gin).

When both had sufficiently imbibed, they embarked from Oyster Pond on the island’s east coast. The Frenchman headed off along the coast to the north, while the Dutchman followed the coast south; wherever the two groups met was where they would draw the dividing line from Oyster Pond.

But as the Dutchman met a woman and stopped to sleep off the effects of the gin, the Frenchman was able to cover more distance, but apparently also cheated as he cut through the northeastern part of the island, and therefore ended up with more land, but that’s history.

Though oft-repeated, the history determined that story is not accurate. During the treaty’s negotiation, the French had a fleet of naval ships off shore, which they used as a threat to bargain more land for themselves. In spite of the treaty, relations between the two sides were not always cordial.

Between 1648 and 1816, conflicts changed the border sixteen times. In the end, the French came out ahead with 21 square miles (54 km2) to the 16 square miles (41 km2) of the Dutch side.

History of Saint Martin / Sint Maarten into the 20th century

The economic decline forces many Saint-Martiners, both French and Dutch into exile. During the history, many emigrated to the islands of Aruba and Curaçao, drawn by the oil refineries set up by the Dutch-British Shell Oil Company in the 1920s. Others emigrated to the Dominican Republic, the US Virgin Islands and the USA. Specialist of the history believe that between 1920 and 1929 the island’s population fell by 18 percent.

Saint Martin – 1939

France and the Netherlands abolished customs duty and indirect taxes between the two zones (Dutch and French), which allowed for unimpeded development of commercial and economic relations between the two parts of the island. At this time, the French administration had very little to do with Saint Martin, except to rescue some soldiers in the two World Wars. It was the Second World War that pulled Saint Martin out of isolation and into the spotlight.

Under the Vichy Regime (1940-1944) a blockade was imposed on allied forces. During and after the War, trade with the United States intensified. The US became the island’s only supplier. This was a lucrative time for many traders, who made their money by selling cigarettes, fabrics and goods in Guadeloupe and Martinique. It was at this time that a climate of self-administration and self-management began to develop, resulting in a blend of local customs, legal vacuums and foreign practices.

Saint Martin – 1943

The site of the present-day Princess Juliana International Airport (Dutch side) became a strategic US airbase and a key weapon in its arsenal against German submarines. And so, the War helped to Americanise and anglicise the population of Saint Martin/Sint Maarten, and English became the working language across the island, competing with French in the north and Dutch in the south.

Saint Martin – 1946

French Saint Martin was included by law in the département of Guadeloupe. The two communes of French Saint Martin and St Barths formed one “arrondissement”.

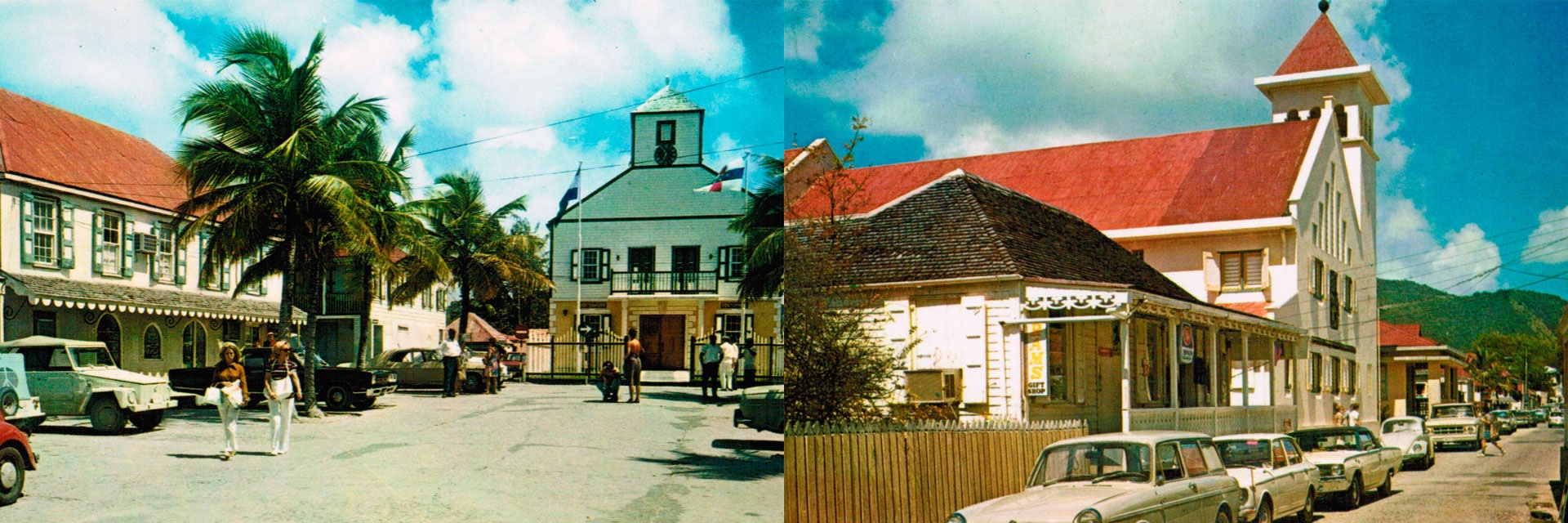

Saint Martin – 1963

French Saint Martin becomes a “sous-préfecture”. It was not until now that the first banks were set up on the island and inhabitants could hook up to the electricity network.

Saint Martin – 1965

The burgeoning tourist industry on Saint Martin benefits from the fresh interest of Americans drawn by the sun, who see the island as the perfect getaway. Between 1950 and 1970, hotels begin to spring up on the Dutch side.

Saint Martin – 1972

Grand Case Airport opens on the French side.

Saint Martin – 1980

The tourist economy is in full swing. The dollar gains great value and only four hours separate Saint Martin from the USA: two major pluses that lead the island’s economic and political stakeholders to realise that they can develop a luxury tourist experience on the “Friendly Island”. Simultaneously, successive tax exemption laws lead to a property boom on the French side.

At the time, Saint Martin offers around 7000 rooms in its hotels, making it one of the most highly-prized destinations in the Caribbean. The island of Saint Martin becomes a cradle of tourism where sun and warm waters, parties and varied events, luxury duty-free boutiques and culinary delights blend with everyday life. However, the boom was rudely interrupted in September 1995 by the passing of Hurricane Luis.

Saint Martin – 1995

Hurricane Luis, on September 5th 1995, annihilated the entire island in the full throes of economic growth. Around twelve people died, hundreds were injured and thousands lost their homes.

Aside from the human drama, the full force of Luis left a desert in its wake, lined with piles of rooves, boats, trees and other detritus. Most hotels and tourist accommodation facilities were destroyed and had to shut up shop, leaving hundreds jobless 1995 will always remain a significant year in the history of the island: for every inhabitant there will always be “pre-Luis” and “post-Luis”.

Saint Martin – New Century

Since 1995, local stakeholders have stepped up their efforts to restore the island to its former glory. And, in spite of a less-than-auspicious global economic context and a series of events that have hampered the development of the island’s tourist economy (Hurricanes Lenny and Georges in 1999, the September 11 attacks in 2001 and the war in Iraq), the “Friendly Island” remains one of the most coveted destinations, unparalleled in the Caribbean, where the local charm, blended with a traditional way of living and one of the warmest welcomes on the planet, draws thousands of tourists from all over the globe.

Saint Martin – 2017

History repeats itself. Hurricane Irma hit the island on September 6th with incredible violence and winds of up to 420 km / h. Television provides viewers with images of chaos that are reminiscent of bombing. It is a devastated island, 95% destroyed with blown-up house landscapes, built-in cars and completely destroyed communication networks.

The Princess Juliana Airport on the Dutch side is severely damaged and impracticable for the delivery of useful relief assistance. Only the airport of Grand Case French side resumes its activity after a few days.

The inhabitants of Sint Maarten must once again rebuild their island. France and Holland will send troops to help both the Collectivity of Saint Martin and the Government of Sint Maarten. But as usual, St Martin will shine again.

Saint Martin – Today

Since 2017, Sint Maarten is rebuilding slowly. The island faces various problems, like the reimbursement of insurances, or the routing of materials and especially the extent of reconstruction due to the amount of damages. The island which lived at the rhythm of its tourist activity sees it on standby in favor of an economy related to the reconstruction.

It will take long months for Sint Maarten to have a similar tourist activity as before Irma, the history will tell…